Table of Contents

- The unfortunate fact is my daughter came by this all-or-nothing approach naturally.

- This fixed mindset way of thinking only snowballed.

- Implicit beliefs shape our behaviour and can have substantial reprocussions.

- A fixed mindset is like “mental baggage” weighing a learner down

- This begs the question why?

- Attitudes towards kids’ failure is a strong predictor of success.

- Based on these findings, what’s a parent to do?

- Parents start by setting the tone. And leading with curosity is a great start.

- Adding the word “yet” is a powerful way to reframe failure.

- Praise can contribute to growth or fixed mindsets.

- No matter the student’s age, there is hope.

Inside: It’s quite common that children want to give up in the face of setbacks and mistakes. These research backed-strategies can promote resilience and a growth mindset.

I was dicing onions and carrots when I heard the sound of ripping construction paper. My head snapped up from looking at the cutting board to my daughter.

“I can’t do anything right!” she cried as she ran upstairs.

Minutes before, she seemed happy and focused, but that had changed in an instant and I wasn’t sure why.

At school pick up, her teacher suggested that I work on her pencil grip and letter formation…

So that night, just before starting my bolognese sauce, I opened up Pinterest and searched for fun ways to work on printing. My daughter decided the one with the Q-tip and tempera paint looked like fun. So I grabbed a couple of pages of red construction paper, wrote out some letters with a sharpie, and watched her trace both the letter A and B…

She seemed thrilled with her progress and precision. All seemed well, so I stepped away to get dinner started. Now my meal prep was on pause as I pieced together construction paper confetti trying to determine what went wrong.

That’s when I saw it. It was clear her hand had waffled ever so slightly and, as a result, her D wasn’t perfect. So she ripped her work up and ran away.

After piecing together what had happened, I followed her upstairs. I understood what it was like to make a mistake and be devastated about it.

Read: Experts say this is the best way to learn to read and love it too!

The unfortunate fact is my daughter came by this all-or-nothing approach naturally.

I was a child who strove for perfection and agonized over my shortcomings.

My earliest memory of this was in fourth grade. I had a homework assignment I struggled with and instead of handing it in my incomplete assignment or asking for help, I went into the cloakroom. And when no one was there, I shoved my duo-tang underneath some old boxes of Christmas decorations.

When my teacher asked me where my work was, I lied and told her I couldn’t find it. It seemed that getting an incomplete was better than looking ‘dumb.’

Despite the propensity to quit or hide when I didn’t understand, I was naturally a good student.

I made the honour roll, got awards, and was well-liked by most of my teachers.

My approach came to a head when I didn’t understand trigonometry.

Instead of asking for help, or pushing myself further, I chalked my struggles with “SOHCAHTOA” up to the fact I wasn’t a math person.

This fixed mindset way of thinking only snowballed.

The more I saw setbacks as indications I was just not good enough, the more I avoided challenges and set performance goals. Meaning that instead of asking for help and practicing trig I focused on French class. In university, I majored in French… not because I loved it, but because it didn’t seem as challenging as other disciplines.

It was a very unsatisfying way to go through life.

As it turns out, my emphasis on avoiding mistakes wasn’t unique to me (or my daughter for that matter). Instead, it is reflective of implicit beliefs held by many.

Read: How to promote success in the child that wants to quit

Implicit beliefs shape our behaviour and can have substantial reprocussions.

Research shows that implicit beliefs, like the belief that intelligence is fixed or can develop over time, shape the way we view and interact with the world (1, 5).

We don’t necessarily catch ourselves thinking this way, but these beliefs shape our behaviour. In the case of my daughter, chances are she did think to herself, “Should I think of myself as no good because my D looks funny?” She just reacted to her mistake and gave up.

A fixed mindset is like “mental baggage” weighing a learner down

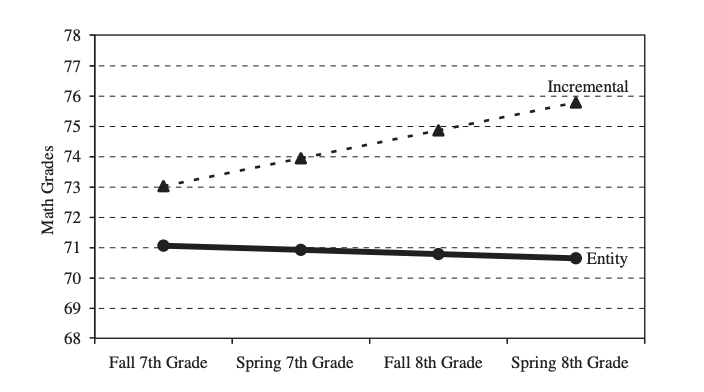

Researchers Blackwell, Trzesniewski and Dweck wanted to look at just how much fixed and growth mindsets impacted junior high students’ academic scores (2). In their two-year study, Blackwell and colleagues found that students who had growth or incremental mindsets believed intelligence could be developed. These students saw a significant increase in their math grades. In contrast, students with fixed or entity mindsets had math grades that stayed stable or dipped slightly over two years. This led them to conclude that mindsets act like “mental baggage” in academic contexts (2,7).

This begs the question why?

Students varying achievement has to do with them adopting mastery or performance goals (3, 6). Namely, students with a growth mindset seek out challenges to build up their academic muscles. Their goals aren’t to appear competent but to master the material. In comparison, students with a fixed mindset set performance goals to demonstrate their competence.

It made sense.

This is why I gravitated towards a degree in French and why I avoided showing my face in classes I wasn’t doing well in.

Attitudes towards kids’ failure is a strong predictor of success.

It turns out that how I handled my failures was consistent with what others with fixed mindsets did. After receiving negative feedback about academic performance, research by Hong and colleagues found students with fixed mindsets were more likely to make generalized attributions about their mistakes (4). For example, they might say, “I am just not good at science.” Or, “I’m not smart when it comes to this stuff.” However, students with growth mindsets were more likely to take the negative feedback and learn from it. They saw their feedback as a sign they should have studied more, they hadn’t mastered the content yet, and that it was a sign they needed more help (3).

They saw these setbacks as opportunities for growth.

Related: The best and worst ways to raise emotionally intelligent children

Based on these findings, what’s a parent to do?

Fortunately, there are plenty of very simple, highly effective strategies that parents and caregivers can implement.

If parents want to give their children a gift, the best thing they can do is to teach their children to love challenges, be intrigued by mistakes, enjoy effort, and keep on learning. That way, their children don’t have to be slaves of praise. They will have a lifelong way to build and repair their own confidence.

– Dr. Carol Dweck

Parents start by setting the tone. And leading with curosity is a great start.

When a child fails a test, stumbles through a speech for school, or doesn’t get picked for the play, there are opportunities to teach resilience and promote a growth mindset. To do this, it is important to approach setbacks with curiosity. It is a great chance to figure out what went wrong and why. For example, failing a math test may mean that a child needs the material explained in a way that is more accessible. Stumbling through a speech at school could be resolved by practicing in front of smaller groups. And not getting picked for the school play may mean a child needs to keep trying for future roles.

Anger, shame, and chastisement have no place here. Instead, parents can use this chance to see room for growth.

In fact, failures can be a change to challenge how both parents and their children view and take on a given task.

In the case of my daughter’s printing practice using the Q-tip, we took turns working on her letters so the task didn’t seem as overwhelming. When tutoring students, I have tried tackling problems in different ways to improve understanding. This can be using manipulatives to teach math or writing about Minecraft to work on spelling.

No matter what setbacks are challenges to overcome.

Adding the word “yet” is a powerful way to reframe failure.

The word yet transforms difficulties from an impossibility into a challenge. In the junior high school example, children in the incremental condition were taught to approach difficulties in math as not having mastered them yet (2,7). Really any failure can be reframe this way. For example, “I don’t understand this material yet.” Or, “I don’t have this memorized yet.”

Adding yet is a powerful way to instill a growth mindset in children as is how parents offer praise.

Praise can contribute to growth or fixed mindsets.

The standard assumption is that all praise is good.

And though there may be some merit to that notion, all praise isn’t created equally. Specifically, research conducted by Mueller and Dweck (6) found that how parents praised their children directly predicted children’s propensity to problem-solve.

Many parents believe that it is important to tell their children how capable they are. Contrary to conventional wisdom, however, Mueller and Dweck’s research shows that children who receive praise for their traits are more likely to adopt performance goals. In turn, successful performance becomes their objective. In contrast, children who are praised for their efforts are more likely to problem-solve and adopt mastery goals – meaning they seek out challenges and strive to learn more. This means children benefit more from praise such as, “Wow! you worked so hard on this” as opposed to “You’re so good at writing.”

Additionally, this body of research found that specific praise about effort predicted a growth mindset. So instead of saying something like, “Great job!” parents can say, “You are so focused on getting this done That’s awesome!”

Finally, parents can help children by urging them to try a different approach or think of the next step. This is far more beneficial than simply saying try harder.

No matter the student’s age, there is hope.

It has been almost four years since my daughter ripped up that piece of red construction paper. Similar to my early university experiences, it was awake up call to teach all of my children that effort matters more than performance. Since that day, I have seen my children’s work ethic get better and better. As it just so happens, I am back in university conquering the demons of my former fixed mindset. This last semester, I took an intermediate course in data science – something I never would have taken years ago. Though it was the hardest class I have ever taken, I showed up to each class, participated to the best of my ability, and completed the course. My grades are better than ever and so is my understanding.

It just goes to show that parents and children only need to make simple adjustments to how they tackle academic tasks. These little changes to our mindset pay dividends.

Related articles you may find helpful:

1 comment